In June, Apple briefly removed nearly all games that featured the Confederate Battle Flag from the App Store. Controversy ensued, with much denunciation of Apple’s move – not all of it in good faith. Apple almost immediately walked back their blanket ban and reinstated apps that Apple perceived to be including the flag for “educational or historical uses”.

So: a relatively short-lived controversy, now many weeks in the past, and almost immediately resolved to the satisfaction of most rational people. Why am I writing about it? Well, I think there’s still a number of issues worth digging into here.

Intention & Ignorance

Firstly, let’s not kid ourselves about Apple’s motives. They are a big corporation that chases the mainstream political zeitgeist in order to be more palatable to their customers, not out of some moral certitude. They didn’t pull any games with swastikas in them back in June. They reversed their decision because they were criticized, not because they’d seen the error of their ways.

There were plenty of people angry about Apple’s action for the right reasons. There were reasonable people genuinely torn about it. There were folks, like the GamerGaters, operating in bad faith – not particularly interested in free speech or education, but in advancing a regressive political or social agenda. And then there were the people who were flat-out ignorant of historical reality. These are the people who have rainbow-ified their Confederate Flag avatars on Facebook and see no contradiction, as though Stonewall Jackson would have been fine with boys kissing boys. These are the game devs who decried the Apple decision by complaining about the “real racists”.

“Heritage, not hate”, these people say. But they don’t understand their heritage. Games can help remedy this.

History’s Value

Let’s zero in on the historical aspects, here. It is the undermining of history that leads to this sort of thinking, whether through deliberate obfuscation of facts or misplaced romanticism and nostalgia. Misunderstanding, whether deliberate or not, leads to the same result; ignorance is only slightly more excusable than malice. Here are some facts regarding controversial conflicts that games deliberately avoid addressing.

The Confederate States of America was a traitorous insurrection founded on slavery. The war was started by the CSA to preserve slavery. Slavery enabled the Confederacy’s armies to remain in the field, and accompanied them to the battlefront. An educated person cannot, in good faith, create a game about the Civil War that does not at least touch on slavery.

Just as slavery was critically important to the Confederacy’s ability to prosecute their war, so the Holocaust and other Nazi atrocities are inextricably linked with Germany’s part in the Second World War. Slave labor helped to fuel the Nazi war machine. Anti-semitism, both by driving out some of Germany’s most intelligent and productive citizens (see: Einstein, Albert) and by the huge diversion of resources and rolling stock necessary for the Holocaust, probably expedited Hitler’s defeat by months or years. An educated person cannot, in good faith, create a game about the European Theatre of WWII without at least mentioning the real consequences of Nazi ideology.

And yet: most games about the Civil War or WWII don’t do this. They not only fail to educate, they deliberately avoid facts that could be seen as controversial. It is, admittedly, difficult to tackle these sorts of issues. Nobody wants a game about the Holocaust, unless it’s about escaping from it or undermining it. Decent human beings are not interested in some kind of Eichmann Simulator, and people who are interested should not be allowed to have it. Still, there are ways to educate players about the more troubling aspects of our past without forcing them to play-act war crimes.

The Symbols

Let’s circle back around to the Confederate Flag and the swastika and their ilk. Do these symbols add meaning and value?

Well, yes. From a game developer’s perspective, symbols have value, even in the hatred they inspire. One of the main draws of games with a World War II setting is the chance to slay Nazis. Players know that the swastika is a symbol of evil. It reminds us of Nazi ideology and its resultant bloodbaths and atrocities. This principle applies to other forms of media, as well. Tarantino’s last two films (Django Unchained and Inglourious Basterds) rely heavily upon it.

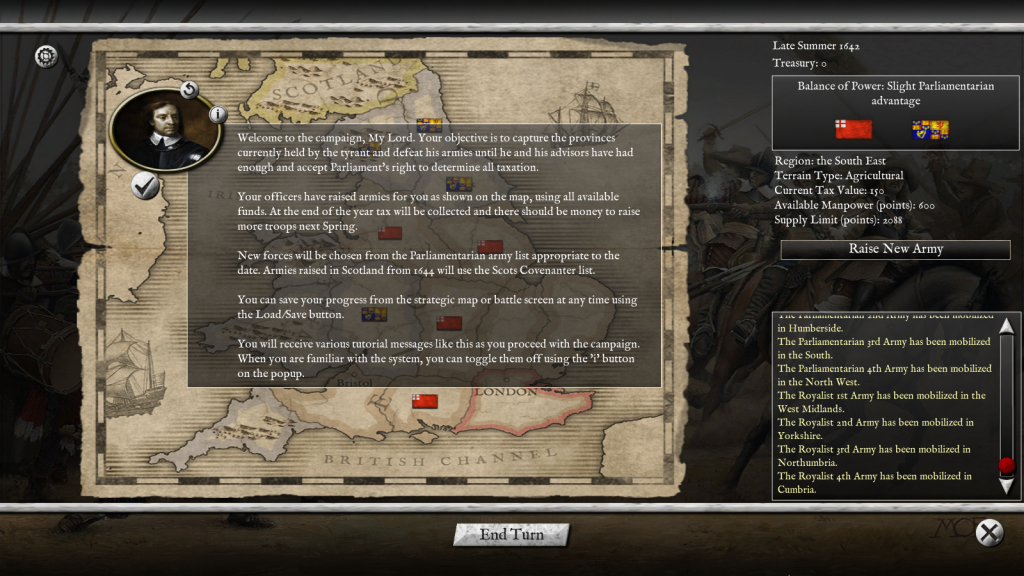

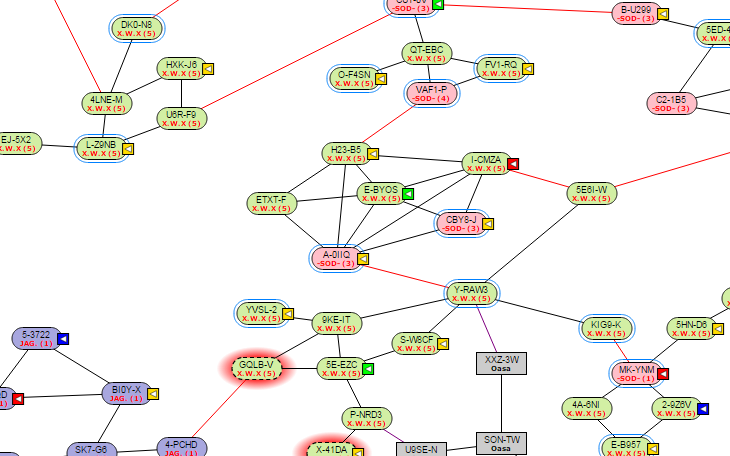

There’s a negative argument in favor of including these symbols, too. Look at what happens in their absence. In Paradox’s WWII Hearts of Iron series, there are no swastikas. There is no mention of the Holocaust or war crimes or massacres. The end result is to suck the morality out of the game. The Nazis become just another nation to play. The Waffen-SS are portrayed not as murderous thugs, but as elite supertroops. In Hearts of Iron III, the tutorial is narrated by Hitler. This is the logical end-result of the Paradox mentality: games that run so far away from history that they become divorced from reality in a disturbing way. Mentioning something like the Holocaust becomes seen as sour grapes and responded to with accusations of “whining” or “that’s not what this game is about!”

Even when media effectively claims a historical setting but fails to include the relevant symbols, things can feel a little defanged. (Remember the idiotic doubled-armed Nazi salute used in the first Captain America movie? I’m sorry, the HYDRA salute.) I won’t wade into the controversy over the Wolfenstein games in Germany here, but similar thinking can be applied.

Of course, there are also games that traffic in and appropriate these symbols to cover for their own creative and narrative failings – with no sign of the victims of said evil. This is part of why the most recent Wolfenstein title was such a breath of fresh air: the Nazis weren’t just bad because they put swastikas everywhere. They did the awful things that Nazis do. This ups the narrative stakes and educates players. It’s good for everyone!

There are limits to this line of thinking. Most symbols are ambiguous, and some are basically unimportant. The swastika and the Battle Flag are uniquely charged with meaning. We can’t pat ourselves on the back for including the Italian flag in a game because of Italian war crimes. But we can say “hey, wouldn’t a strategy game based on the second Italo-Ethiopian war be cool? Let’s make it, and be sure to include the use of chemical weapons – it’d be disrespectful to whitewash history for the sake of a modicum of mainstream acceptability.”

Myopic Accuracy, Educational Dissonance

Above is an interesting screenshot from the upcoming Decisive Campaigns game. How should I feel about having a “Good” relationship with the most infamous man of the 20th century? Um, probably not great! And that’s good! If you’re playing as a German officer in WWII, you should feel the dissonance of winning for evil. Only STAVKA-OKH has managed this.

Yes, historical wargames have an obligation to remind the player that war isn’t a game. Historical shooters have an obligation to teach us why we’re shooting. War is as much about moral choices as it is strategic or tactical ones. This is something the Total War games (which I’m generally not a fan of) do surprisingly well, in oblique ways. When a city is captured, the player must choose whether to Raze, Loot, or Occupy it. There are benefits and downsides to all three options, but it is made clear that by clicking the “raze” and “loot” buttons, you are effectively condoning the murder of civilians. I could never bring myself to do anything but Occupy, but the fact that the choice was there made me morally aware. It helped educate me about the stakes and consequences of conflict.

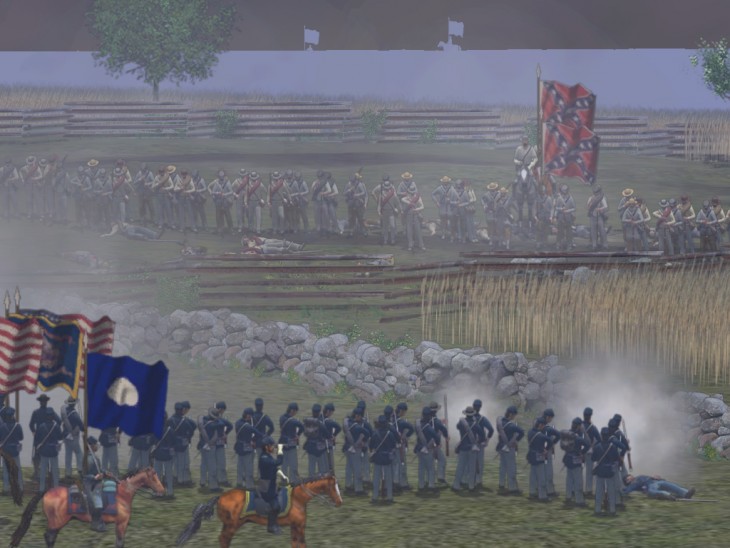

When you win Sid Meier’s Antietam or Ultimate General: Gettysburg, you should have a sour taste in your mouth, because you haven’t just won a battle, you have defended and extended the practice of human bondage. This isn’t preaching or moralizing – this is accurate. Not the myopic accuracy that enables a game like War in the East to model every aspect of the Nazi war machine, every piddling variant of Panzer, without acknowledging the monstrous actions of both sides of the conflict (and the flag that flew over one of them).